The Application of Photography to Printing

In the beginning of the 1840s the rising employment use of wood engravings, initiated by Thomas Bewick, fostered an effective use of images in editorial and advertising communications. Wood engraving dominated book, magazine and newspaper illustrations. The reason for this being that wood-engraving blocks were type-high, could be locked into a letterpress and printed with type, whereas copper and steel engravings or lithographs had to be printed as a separate press run. Although wood engraving printing blocks were favored amongst printers, the preparation of these blocks were very costly. Due to this inventors continued their search for an economical and reliable photoengraving process for preparing printing plates; a process already begun by Niepce.

In 1871 John Calvin Moss of New York invented a commercially achievable photoengraving process for translating line artwork into metal letterpress plates:

- A negative of an art piece was made on a copy camera suspended from the ceiling by rope to prevent vibration.

- This negative was contact printed to a metal plate, coated with a light sensitive gelatin emulsion, using a highly secret process

- The image was etched with acid.

- It was hand-tooled for refinement

- Lastly, it was mounted onto a type-high wood block.

The more this process was implemented, the more costs and time required to make the printing blocks were reduced. Greater fidelity to the original was achieved.

Photographs were only used as a research tool for developing wood-engraving illustrations before it was possible to print them. Photograph’s documentary reality helped to record current events. In the 1860s and 70s wood engravings drawn from photographs became common in visual communications. Matthew Brady’s works are good examples of this wide spread method.

To capture one his famous images he turned his camera upon a group of slaves who suddenly found themselves to be freed men when the Union forces broke through the Confederate defenses of Richmond, Virginia in 1865. He preserved a moment in time. The image was a historical document to help people understand that their history was formed with the timeless immediacy of photography.

Seeing as the methods to reproduce this image were not yet available, Scribner’s magazine hired an illustrator to translate the image to a wood engraving to render it reproducible.

|

| Mathew Brady, 1865, "Freedman on the Canal Bank at Richmond". The photographer supplied the visual evidence needed by the illustrator to document an event. |

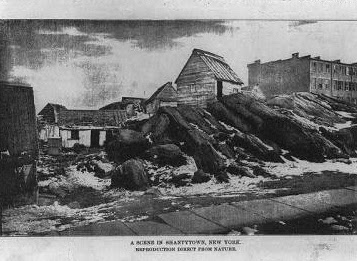

In 4 March 1880 a breakthrough occurred when the New York Daily Graphic printed the first reproduced photograph with a full tonal range in a newspaper. This image was titled A Scene in Shantytown. Stephen H. Horgan invented the crude halftone screen it was printed from with perforated cardboard. During this process the perforated screen broke the image into a series of minute dots that varied in size. The sum of all the minute dots produced the illusion of continuous tone. Values from pure white paper to solid black ink were simulated by the amount of ink printed in each area of the image.

- Parallel lines were inscribed on optically clear class, which had an acid-resistant coating, using a ruling machine.

- The ruled lines were etched into the glass using acid.

- These indentations were filled with an opaque substance.

- Two pieces of ruled glass were sandwiched together, face-to-face, with one sheet’s lines running horizontal and the other running vertical.

The amount of light passing through each little square, formed by the crossing lines of the glass sheets, determined how big each dot should be. The era of photographic reproduction started as halftone images could be made form these screens.

The 1881 Christmas issue of the Paris magazine called L’llustration showcased the first illustration to be printed using a photomechanical process. This method of photomechanical color separation was costly and time consuming. Thus it remained in it experimental stages until the end of the 19thcentury. In these stages it almost completely replaced the jobs of the craftsmen who transferred artworks to handmade printing plates. To make a printing plate by hand took up the a week. By using photographic processes, this time was reduced to only a few hours. Eventually this process reduced costs, associated with manufacturing printing plates, tremendously.

Comments

Post a Comment